“Merely having an open mind is nothing. The object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.”

-G.K. Chesterton

There’s a modern temptation—one that perhaps academics are particularly susceptible to—to equate intellectual humility and a sort of agnosticism…a receptivity to alternatives…a willingness to entertain all viewpoints. The less convictions, the better. After all, we are limited beings (whatever that means). And conversely, robust convictions and an unwillingness to take seriously alternatives, no matter how outlandish or reprehensible, has become the capital vice—it encapsulates the single, great error that Enlightenment thinking freed us from.

Apart from perhaps the oversimplification of the history of philosophy I painted above, the overall diagnosis of modern sentiments regarding open-mindedness and intellectual humility strikes me as fairly accurate…otherwise, I wouldn’t have said it.

A quick Google search for “intellectual humility” yields pop articles like those in Vox and The Cut that tell us intellectual humility is simply “the recognition that the things you believe in might in fact be wrong” and about “understanding the limits of one’s knowledge. It’s a state of openness to new ideas, a willingness to be receptive to new sources of evidence.” Even a couple of recent philosophical accounts defend what’s called the “limitations-owning” view (Rushing 2013 & Whitcomb, et al. 2015).

The points of emphasis in these modern accounts of intellectual humility are receptivity to alternative viewpoints and owning one’s limitations and fallibility. In other words, don’t hold onto your beliefs too tightly for you may be wrong. So, we can say that modern accounts of intellectual humility are characterized by emphasizing the disposition of epistemic “refraining”. Refrain from forming beliefs and convictions and you’re good to go.

The problem is that this picture is incomplete. Of course, intellectual humility involves not believing more than the evidence warrants and tempering one’s confidence in one’s beliefs if the truth really is elusive. For example, it’s arrogant, and pretty silly, to strongly believe that there is an odd number of stars in the galaxy. The evidence in this case underdetermines—we simply don’t have enough evidence to conclude that.

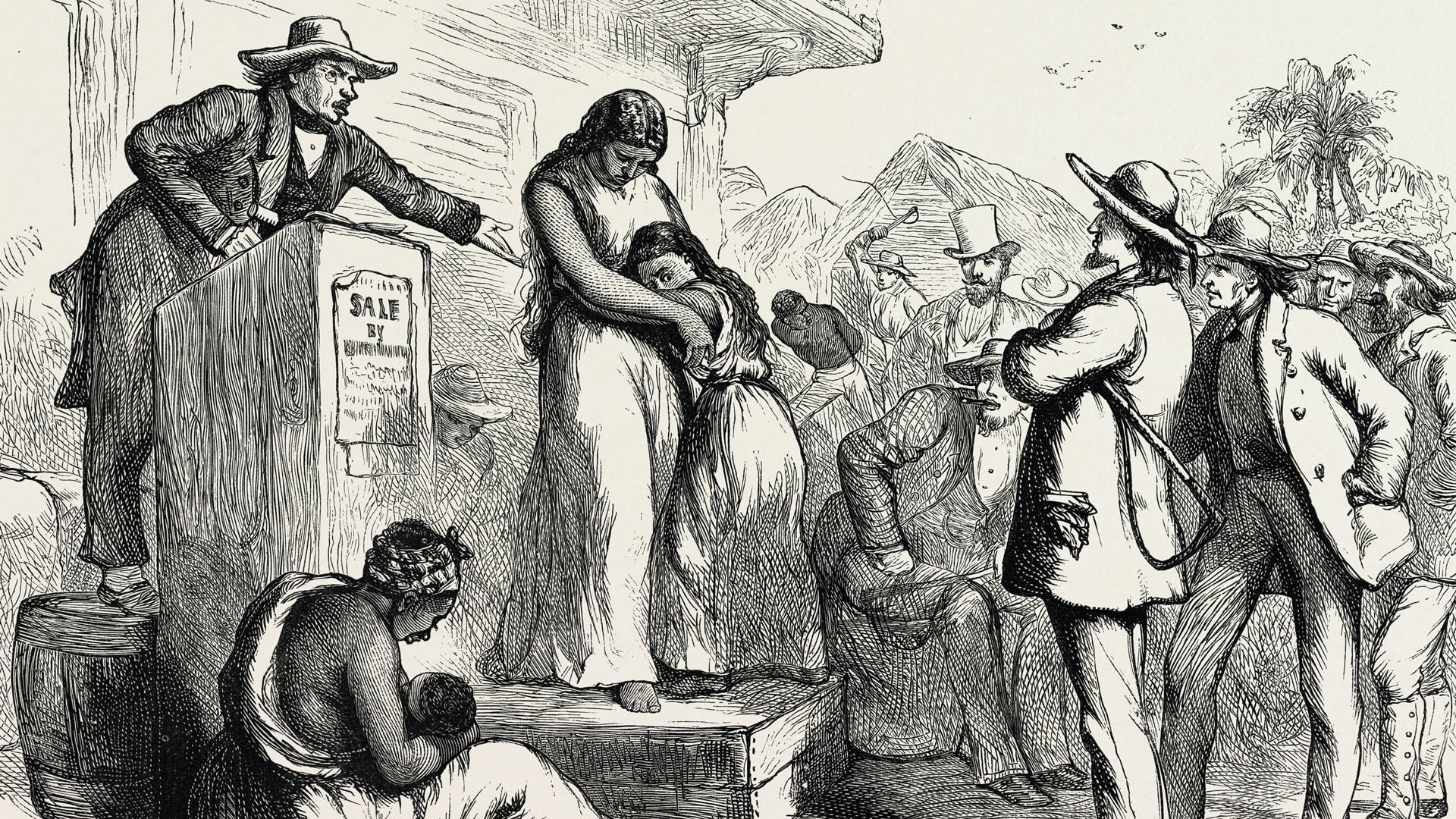

However, there is an underappreciated dimension of intellectual humility that isn’t captured by these “refraining” accounts. Take the following quote about slavery from the famous American abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison:

I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject [slavery], I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation. … I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD.

Garrison’s sentiment expressed here is the paradigm of intransigence and unwavering conviction— “harsh as truth” …”uncompromising as justice” … a refusal to moderate, equivocate, excuse, or retreat.

Is Garrison failing to practice intellectual humility? Is he intellectually arrogant?

No!

The evil of slavery demanded such an unequivocal response. Justice demanded that unwavering conviction about the equality of all persons.

This example nicely draws out an important, yet oft-overlooked, insight about the nature of intellectual humility. It’s not primarily about epistemic refraining, rather it’s about submission to truth. To be intellectually humble is to accord one’s mind with reality. It’s to follow the evidence where it leads. It’s not arrogant to form an unwavering conviction that slavery is evil and a terrible affront to human dignity. On the contrary, it is arrogant to refrain from forming an unwavering conviction that slavery is evil and a terrible affront to human dignity. It’s arrogant to adopt an agnostic disposition when the truth is staring you in the face. It’s arrogant to witness oppression, extortion, and degradation, and in the name of pseudo-intellectual humility say that we just “don’t know” whether that’s really wrong.

The 20th century French philosopher, Etienne Gilson, puts it nicely:

“Philosophy does not consist of encouraging others to continue in false beliefs, and the worst way of persuading others to abandon their error is to appear to share the same error. There is only one truth, the same for all, and the highest good for a rational being is to know the truth. When a philosopher sees the truth he can only submit himself to it, for that is true wisdom; and when he has discovered the truth, the best thing he can do for others is share it with them, for that is true charity.”

Truth-seeking is not only not incompatible with intellectual humility—it is a defining feature of it. Refraining from taking a position is only permissible if the evidence warrants doing so. To believe more than the evidence warrants is intellectually arrogant. But to believe less than the evidence warrants is also intellectually arrogant.

It takes humility to accept or be willing to proclaim a truth that one’s politics or persuasion finds unpalatable. Unfortunately, a lack of this humility is often combined with intellectual dishonesty which leads to the maintenance of entirely unsupportable positions defended only by crying “hatred” or “bigotry” when confronted with the truth. Great piece, my friend.